How I created an AI that can (partially) play the platformer game Celeste

Published:

CelesteBot Development Blog, Part 1

Introduction

This is the first in a series of blog posts about the Celeste AI I am developing using PPO Reinforcement Learning. In case you aren’t familiar, Celeste is an indie platformer game known for its difficulty and fluid but precise controls, which make it stand out from traditional platformers such as Super Mario Bros that are designed with a broader audience in mind. The game is available on Steam and Nintendo Switch. Celeste has become somewhat of a cult classic to its fans, and maintains a substantial speedrunning and modding community even though it came out over 5 years ago.

In fact, the plethora of tools and knowledge cultivated by the modding and TAS (tool assisted speedrun) community is what made this project possible. I’m grateful for their assistance answering my questions on everything from debugging to finding the right tools to use. The project relies on a modding framework for Celeste called Everest to create a mod that allows the AI to both control and read the game state directly through code. I originally forked the project from an earlier attempt by sc2ad to create a Celeste AI. I mostly used their code for controlling Madeline (the main character) and for the code that allows the AI to read the game state. The code for the AI itself is entirely my own, and relies on a Python interconnect to RLLib from the C# code that controls the game using PythonNET.

Why Celeste?

I have wanted to create a Reinforcement Learning algorithm to play a game for some time now, but choosing the right game for doing so is a challenge in itself. I ended up choosing Celeste because of the tools made by modding community and because I wanted to stretch the limits of RL with a game much more challenging than the average platformer. Despite its difficulty, it’s a relatively simple game for AI to understand and learn to play since it is 2D, and only has a handful of controls with no analog controls (eg, a mouse or joystick). More complex 3D games are much more difficult to implement, and would require large clusters of GPUs to train.

Reinforcement learning relies on three key components: a representation of the inputs to the game (the controls), an easily interpreted representation of the game state, and a reward function based on the game state.

Out of these three, efficiently representing the interpretation of the game to the AI can make or break the viability of the project, since a very large deep network would be impractical to train. The reward function also has its own challenges: it must accurately reward and punish the agent’s actions in every potential situation. A suboptimal reward function will result in the model never learning to play the game properly, such as jumping around in place for hours to avoid a negative reward associated with death.

Usually when developers create an RL agent for a game like Celeste, the game state is represented by screenshots of the game fed directly into a convolutional neural network that represents the Policy of the AI. Additionally, in order to play the game well, the agent needs to be able to make at least 6 actions per second, which further restricts the size of the convolutional neural network to represent the game if I wanted to train it in a reasonable amount of time.

Training speed is essential to this project, as iterating on the algorithm would take far too long if I had to train the agent for days or weeks at a time. However, thanks to the modding framework, I could directly extract the game state from memory, which helped me create a much more efficient representation of the game state.

By extracting the tiles that represent objects in the game, I can fully represent the current game state in only a 40x40 tile grid. Furthermore, rather than relying on RBG or grayscale colors to represent each tile, each pixel is represented by the ID of the specific tile. For example, the character is Tile ID 1, Air (empty space) is ID 2, and so on. This simple game state representation allows me to train the AI much faster than if I had to train it on screenshots of the game.

The developers also created the game to be intentionally difficult, but forgiving so that players would be able to iterate on their mistakes and learn. When the character dies, you only ever reset to the beginning of the screen you died on, and there is no life or health bar like in traditional platformers. The idea of trying over and over and learning from your mistakes is essentially how reinforcement learning actually learns as well, so the human-centered game design also benefits AI!

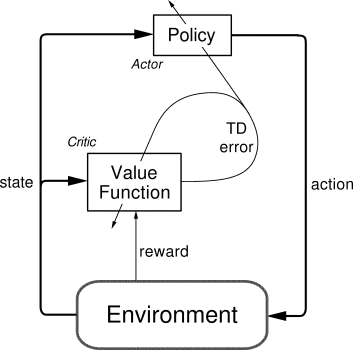

The Policy

Now to get into the meat of the RL algorithm: The Policy. Model-free reinforcement learning differs from other ML techniques in that the learning algorithm is actually separate from the model itself. Actor-Critic algorithms, a form of model-free learning, predict the best action from a game state as well as the expected reward from an action/game state combination. Actor-Critic policies allow the model to teach itself both how to act and how to evaluate its own actions, a key component in the learning process.

The RL algorithm itself is responsible for training the Policy to make actions that will maximize the reward function for a particular game state. For example, reaching the end of a level would provide a positive reward, and dying far away from the end of the level would give a negative reward. Actor-Critic RL combines both value-based and policy-based RL, which means that the RL algorithm also trains a separate value function that predicts the expected reward if the agent takes a specific action in a given game state.

Researchers in recent years have iterated on several Actor-Critic algorithms for training reinforcement policies. For Celeste, I chose to use Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) created by OpenAI since it is a performant algorithm that still meets the criteria of stabilizing the policy function on any given training batch.

PPO is an on-policy algorithm, which means that it only uses data from the current Policy to train the Policy itself. This is in contrast to off-policy algorithms such as Deep Q-Learning, which send external or random data to the game in order to explore new techniques. PPO uses a stochastic sampling algorithm to explore new techniques semi-randomly, which allows it to explore new techniques while still integrating some knowledge from the policy learned so far.

As mentioned before, Celeste is a very difficult game, which means the policy algorithm must have the flexibility and sophistication required to learn complex new techniques and combinations of controls. However, it’s also important that the learner does not forget old techniques that it already mastered due to an over-eagerness to reward or punish certain actions during training. PPO is designed to balance between these two extremes, and works well for both learning new strategies through its stochastic action sampling, while avoiding infamous “catastrophic unlearning” of other policies like DQN by limiting the amount of change to the policy during a particular training step. PPO is also a well-proven algorithm across many domains, from defeating the best human players at DOTA2 to refining ChatGPT to give more human-like responses.

The Reward Function

The goal of any reinforcement learning agent is to maximize the expected cumulative reward, called return, by choosing the best action at each step. The reinforcement learning algorithm updates the policy based on the agent’s experiences of states, actions, and rewards. The reward function is a subjective choice based on the goals of the agent and essentially encodes the goals of the agent. Since the reward is automatically calculated in a function for every game state, this means that the RL agent teaches itself to play the game without any human input! 1

For CelesteBot, I chose to use a reward function that rewards the agent for moving towards the end of the level, and penalizes the agent for dying based on how close to the goal it reached. The reward function is calculated by taking the difference in positions between the current game state and the previous game state, and then adding a reward for moving towards the end of the level and subtracting a reward for dying. The reward function is also scaled by the number of frames that have passed since the last reward was given, which essentially means that the agent is rewarded for moving towards the end of the level as quickly as possible.

Here is some pseudocode for the reward function:

def reward_function(current_state, previous_state):

# Calculate the difference in position between the current and previous state

delta_x = current_state.x - previous_state.x

delta_y = current_state.y - previous_state.y

# Calculate the reward for moving towards the end of the level

reward = delta_x * 0.1 + delta_y * 0.1

# Reward the agent more for exploring further than it has reached so far in the current episode than it is punished for moving away from the end of the level

if furthest_reached_in_level(current_state):

reward *= 4

# Calculate the reward for dying: Reward is scaled by how close to the end of the level the agent was

if current_state.dead:

reward -= 1000 * (1 - delta_x / level_width)

# Scale the reward by the number of frames that have passed since the last reward

reward *= 1 / (current_state.frame_count - previous_state.frame_count)

return reward

Disclosure: GitHub Copilot helped write this pseudocode based on the original function.

The agent is rewarded much more for discovering new paths towards the goal than it is punished for moving away from the goal to encourage exploration by backtracking when necessary. I also break down the change in position into x and y components, and reward the agent as long as it moves towards the goal in at least one dimension.

Most of the time while playing the game normally, you are moving either up and down or left and right, so it doesn’t make sense to heavily reward the agent for moving diagonally. There are also situations where sometimes you have to backtrack to make progress, so I don’t want to punish the agent too heavily for moving away from the goal in a certain direction.

One meta-problem with the reward function when learning to play the game normally is that the first 2 chapters require moving up and to the right, whereas later in the game the player needs to move in many other directions. The result is that the initial version of the agent tends to always try to go up and right even if the level is meant to go from the right to the left.

The solution to this is to train the agent on a variety of levels in a random order, which should help the agent learn to move in all directions. The next stage of the project will use the Celeste Randomizer to generate a random order of levels to train the agent on, which will help the agent learn to play in any given level at the cost of slower overall training.

Overall, the reward function essentially rewards moving towards the goal very quickly and especially towards areas it hasn’t reached before. This maps to how a human would play the game normally, as even regular players don’t usually waste time while playing games by going back and forth before going to the exit. The agent also learns to avoid dying early in the level, but can actually be rewarded for dying very close to the level. Over-punishing death results in an agent that’s too afraid to learn, and just like a human player, the agent will have to die many times in order to learn how to play the game.

The Policy Model

Finally, the Policy model itself is a neural network that takes in the game state and outputs the best action to take. The Policy model is a convolutional neural network that takes in a 40x40 pixel grid representing the game state, and outputs the best action to take.2 I also added several attention layers to the model in order to create a sense of “memory” in the neural network, similar to how LLMs learn language data. These attention layers are essential to learning a more difficult game like Celeste, since they allow the agent to use past actions and game states to help understand what to do in the future in the same way a human would play the game. The model is trained by the PPO algorithm described earlier. Unlike traditional deep learning, designing the deep model itself is a much smaller part of the overall project, since the PPO algorithm is mostly responsible the quality of the trained model.

Model Architecture passed through RLLib, provided for those familiar with Deep Learning:

{

"conv_filters": [[16, [3, 3], 2], [32, [3, 3], 2], [64, [3, 3], 1]],

"attention_dim": 256,

"attention_head_dim": 128,

"attention_num_transformer_units": 6,

"attention_memory_inference": 50,

"attention_memory_training": 50,

"attention_num_heads": 6

}

Parallelized Training Architecture

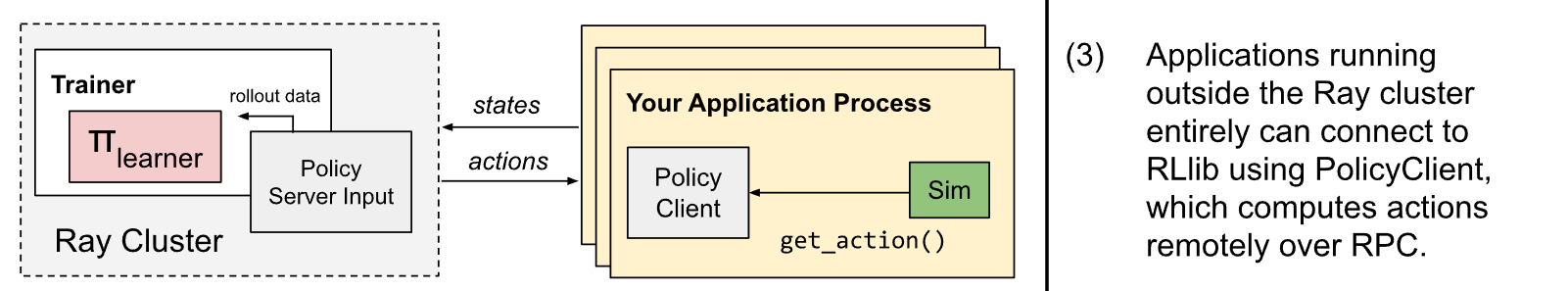

As mentioned before, the three key components of reinforcement learning are the controls, the game state, and the reward function. However, in order to scale the training of the AI, I created high-level three components to manage the overall system architecture: the game client, the reinforcement learning server for training and inference, and the interconnect between the game client and the server. By separating the game client process from the RL algorithm, I can run several instances of Celeste at once to parallelize the training of the RL algorithm.

The overall architecture as well as the RL algorithm itself are implemented using RLLib, which is a reinforcement learning library built on top of Ray. RLLib is a great library for distributed reinforcement learning, with several operating modes that allow you to train the RL algorithm across several instances of the game at the same time. Although I only had one computer, I used the server/client mode to train the RL algorithm across multiple game clients at once, which reduced training time for a basic agent from around a day to a few hours.

A single server process managed all the RL training and inference from game states and rewards received from several game clients, which hooked directly into an instance of Celeste. The PolicyClient is in Python, and connects directly into the game code to retrieve game state data and provide control inputs using PythonNET. The server process itself manages one child process per PolicyClient to handle inference, and another process for managing the training of the model itself.

Thanks to having 128GB of RAM and a beefy desktop CPU/GPU, I could run between 4 and 9 instances of Celeste training at once, depending on the complexity of the Policy model. As an additional benefit, since the server receives game state data from several games at once, each individual training mini-batch was less prone to overfitting to a particular level or game state than if I had only used a single instance of the game.

Other Optimizations

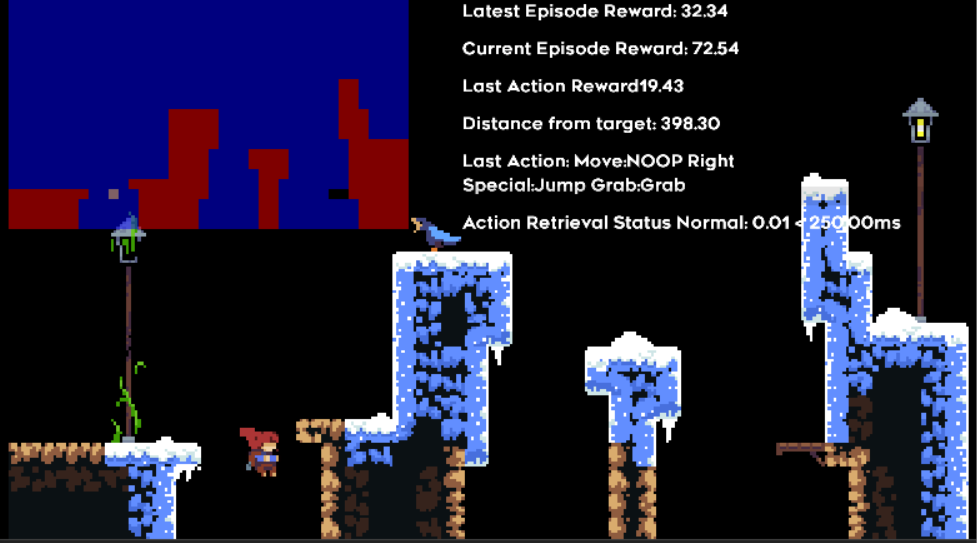

As you may have noticed from the sample video, the game runs much faster than normal speed and has no special graphics or textures. During training, the game runs at 4-10x the normal speed in order to increase the training speed per game client instance. The code for this is very simple, and essentially runs the entire frame calculation loop N times every normal frame, where N is the speedup factor.

For optimizing the graphics, I extracted the SimplifiedGraphics optimizations from CelesteTAS in order to only display the very minimum needed to understand the game visually. These optimizations remove all the “fun” graphics that add to the experience of the game, but don’t provide any gameplay value.

Results and Next Steps

With all the pieces in place, I was able to train a basic agent that could beat the first 1.5 chapters of the game. I used the Population Bandit 2 search algorithm in order to tune hyperparameters, which helps the agent learn much more efficiently. The agent is able to learn how to beat the first chapter of the game, but struggles to learn how to beat the second half of the second chapter. The total training time for the agent was around 8-12 hours, which is much faster than I expected!

This initial stage of this project centered around creating the framework to interpret the game state and to create a basic agent that showed that the concept of an RL agent playing Celeste is possible. However, the levels that come after the first 2 chapters are much more difficult than the levels it has learned to play so far. The next part of the project will focus on improving the agent’s ability to learn to play the game by improving the model architecture and training process, such as through the level randomizer I mentioned earlier.

Solving the Meta-Exploration Problem

Another large problem I haven’t mentioned yet is that the agent can learn how to beat a level by reaching the goal of the level, but it doesn’t know how to choose the end of the level! So far, I have manually encoded the coordinates of the ends of levels as a stopgap, but this would quickly become very labor-intensive and somewhat defeats the purpose of an autonomous agent.

One solution would be to train a separate model to predict the end of the level, and then use that model to choose the end of the level. However, this would require a lot of extra training time, and would require a lot of extra work to integrate the two models together.

A simpler solution is to make the goal of the agent to be the opposite side of the screen it’s currently on, but this would only work for linear chapters. Some of the later chapters require revisiting earlier screens and taking non-linear paths to the end of the level, so this solution wouldn’t work for those levels.

However, I have come up with a more novel solution that would solve the problem without requiring a large amount of extra effort on my behalf, and would truly make the bot an autonomous agent. In order to get there, I took a step back to understand the problem from a higher level.

Essentially, the RL agent can learn how to beat a particular level, but it doesn’t actually know what the game of Celeste is the way a human understands it. For example, if a human is playing the level which branches out into several additional levels, but requires the player to revisit the original level, the human would understand the purpose of the level based on the context of the game, and potentially online resources if they got stuck.

This kind of logical reasoning task is traditionally very difficult for most AI to accomplish, especially one as simple as the deep neural network I’m training. However, LLMs such as GPT4 have the logical reasoning capabilities to accomplish this kind of task. For example, consider the following prompt:

You will now be playing as a “Driver” for an human who is playing through levels of the game Celeste. The human will play through the level, but you are responsible for which adjacent room to go to next, based on information about the game and information given to you about recent rooms visited.

We’re in Chapter 0 Prologue. Here’s some information about the chapter “# Celeste Prologue Walkthrough

- Start: Go right and jump over the falling blocks.

- Section 1: Climb up the wall and wall jump to the right. Run across the collapsing bridge and jump to the right.

- Section 2: Climb up the wall and wall jump to the right. Run across the collapsing bridge and jump to the right.

- Section 3: Jump over the fence and go right. Dash to the right and land on the platform.

- Section 4: You have completed the Prologue!”

We’re starting in the prologue, and the player is in the first room. There’s one room to the left and to the right. The player is at (100, 100) and the level is a rectangle whose bottom left is at (100, 100) and top right is at (1100, 700). What’s the target coordinates for the player to aim for next? Answer in coordinates corresponding to a side of the rectangle where the player should go. Don’t include any additional text, respond exactly in the format: “(X, Y)”

Prompting GPT4 in this manner essentially asks the LLM to use its a human-level understanding of what it means to actually play a video game to reach the goals of the game. From my testing, for simpler levels it provides the correct answers. The walkthrough itself was generated with GPT4 by summarizing walkthroughs available online, and the coordinates are taken directly from the game state. Since GPT4 provides coordinates for the goal of the level as an output, the RL agent already knows how to use the information it provides!

However, this method is not guaranteed to work for more complex situations, and will require more time and iteration to get right. I’m excited to see how this project progresses, and I hope you are too! I will return with a Part 2 once I have more updates to share.

Conclusion

When I first started this project, I estimated it only had about a 30-40% chance of success in a few weeks of continuous effort from one person. Thanks to the modding community, open source RL libraries, and the cumulative effort of the AI research community, it turned out to be far more doable than I originally anticipated! The body of work presented here represents around 100-150 hours of work, and already has solved many of the hardest roadblocks facing a successful Celeste AI that can beat the game completely. I had a great time learning to use the modding frameworks, RL frameworks, and sharing it with the community. I even hosted silent Discord streams where a few people watched the bot learn to play the game for hours at a time, which was a lot of fun.

If you’re interested in learning more about the project, check out the GitHub repo. You can even make contributions of your own! I’m also happy to answer any questions you have about the project, so feel free to reach out to my contact information in the sidebar.